Benefits of a ’smart’ power grid in South Florida debated

A ’smart’ power grid for South Florida would ease usage at peak times, but the payoff for consumers — and the environment — is debatable.

When Kevin Linn of Coral Springs received a special power meter last October, he was able to check his usage day by day and hour by hour via the Internet. He found spikes in midday when no one was home — the water heater was churning away. And he discovered his pool pump was costing more than $50 a month.

He adjusted the water heater to operate only from 5 to 7 a.m. and 8 to 10 p.m., the times his family of four needed hot water. He swapped the pool pump for a more efficient model. So far, FPL records show that he’s saving about $13 a month, but Linn reports, “My bills are $100 a month less than my neighbors’.”

Linn’s experience may be what awaits residents of Miami-Dade County, all of whom are expected to get smart meters in the next two years as part of an ambitious project by Florida Power & Light to create what Miami Mayor Manny Diaz has called “the first truly smart-grid city in the nation.”

The grid concept thrills few voters, but many leaders say it can save consumers money and help combat man-made climate change because the fastest and cheapest way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is to use less electricity.

President Barack Obama’s economic stimulus package includes $4.5 billion to finance such smart grids nationwide. FPL hopes that up to half of the $200 million it plans to spend on the Miami-Dade project could be financed through stimulus funds.

REALLY CHEAPER?

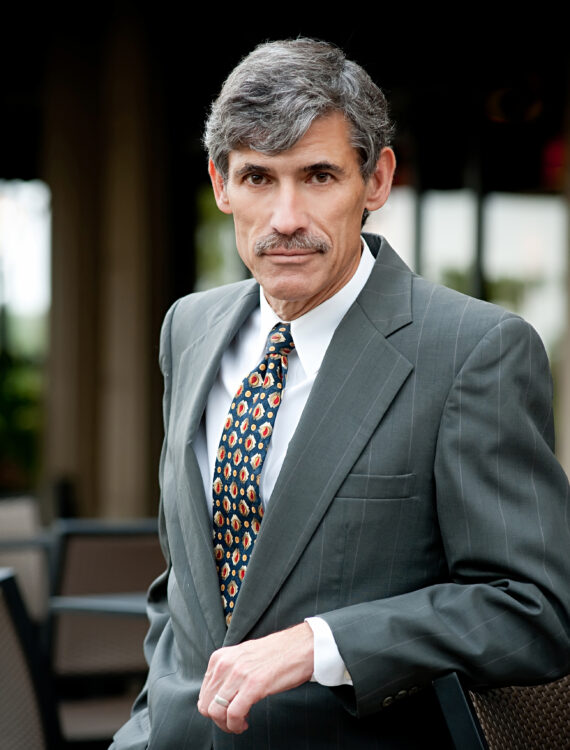

”The devil’s in the details,” said Stephen Smith, executive director of the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy. “If smart meters lead to smart consumers, that’s a very good thing. . . But most utilities are more interested in getting people off peak power, not necessarily reducing their overall usage.”

Indeed, a future phase of the smart grid will warn consumers that the peak period, usually 3 to 6 p.m. in the summer, means more expensive power for the utility and that expense could be passed along to the customer.

But that phase is still down the road. ”The transition to smart grid is an evolution,” said FPL spokesman Scott Blackburn. Over time, “the grid will become more like an intelligent, interactive Internet and less a passive, one-way power system.”

The first step, already tried in a pilot project of 100,000 homes in northern Broward, is to install the smart meters.

A wireless chip in the meter transmits usage to the Web. Residents can use their computers the next day to check their power consumption hour by hour. Over time, they can study, like the Linn family, what their power usage is, and make adjustments to save money.

OLD HABITS DIE HARD

For some families, that may be easier said than done. Many Americans love their gadgets and are loath to abandon them. FPL reports that over the past two decades, despite many energy-efficient appliances entering the market, usage per customer increased by 20 percent. Computers in so-called ”sleep mode,” cellphone chargers, DVRs constantly on — all of these soak up power.

Only during the recession has that usage taken a small drop.

Linn notes that his Coral Springs neighbors have smart meters too, but they don’t seem to be paying much attention to their usage. His bill is generally $100 a month less than theirs, though they live in similar houses.

On average, FPL reports, when consumers nationwide get smart meters, their usage drops about 5 percent per month.

“SMART APPLIANCES’

In a second phase for a smart grid, homes will eventually get ”eco-panels” that will be able to control and time many ”smart appliances” within a house. The key here is minimizing usage during peak periods, when electricity is more costly to FPL than during the rest of the day.